22 February 2025

Engineer Experience

by Slava I. Maslennikov

Are you maximizing a fulfilling environment for your engineers?

If you’re reading this, you probably care about your organization’s engineering culture. I’m available on a full-time and contract basis to help you: shoot me an email!

An engineer’s needs

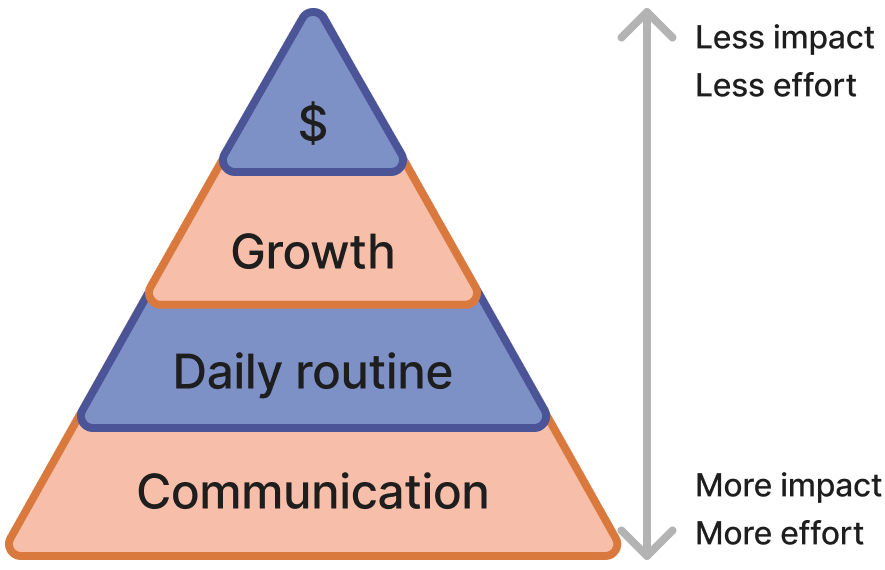

The goal of this blog post is a discussion of retention of talent most crucial to a company’s engineering success and progress. In other words, we’re talking about a long-term game for your engineering department: short-term engineering needs can be satisfied by reversing the pyramid.

Placed on a hierarchy of needs, an engineer’s primary needs are high quality interactions. Not to say that engineer’s paycheck can be fully substituted by kindness: rather, the former can’t replace the latter in a long term proposition.

From another point of view, the higher you look in the pyramid, the more short-term the solutions will become. Lower, more basic offerings, satisfy longer-term needs.

In terms of implementation effort: the smaller the impact, the less effort is necessary to provide it. For example, increasing a paycheck in a toxic team culture is a click of a button, whereas fixing or creating kind engineering culture will take months of effort from multiple levels of leaders, not to mention the recruitment costs.

In the following sections, we’ll break down what each part of the pyramid implies and list some examples.

Communication

Communication is a crucial component of engineer experience: it’s the good and bad of every day that affects people most. This includes interactions with peers, leadership, and the immediate manager. This is also a question of whether managers, peers, and leadership have your back: in client interactions, leadership decisions, even tooling selection. Engineers and their leaders don’t have to like each other or vibe together: but there must be mutual, equal respect and clarity of value. In fact, maintaining a staff of most likeable people is a major bias, as it reduces diversity of thought.

Clear communication between levels is another basic necessity: purpose of every action has to be clear. Translating business needs in clear terms to engineers is the most important ability every people manager should have.

Some of the questions you may ask yourself on this topic include:

- Is there a feedback loop with regular surveys? (More on this at the end)

- Is there regular communication between the entire engineering team, globally? Is anyone left out?

- Are there regular knowledge-sharing sessions? Do all engineers and some leadership participate in them?

- Is upper leadership paying attention to the quality of people management skills within people managers? How?

Daily routine

Daily routine refers to three categories:

- Ease of engineering

- Bureaucracies

- Projects

Let’s break these down.

Ease of engineering

This mildly intersects with the upcoming Growth section. It’s crucial for engineering members to be able to perform research and development with ease, to test approaches to problems outside of client or production environments. Engineers should also be motivated to talk about these achievements, and share findings through demos. Unless core intellectual property would be exposed, or business would come to harm, these demos should be public and external: this helps company visibility of high quality engineering culture, and promotes engineer growth and visibility.

Bureaucracies

Bureaucracies are the daily processes that are a business necessity, such as filling out time sheets, submitting and tracking PTO. Additionally, this is the ease of following policies and any other painful but necessary “busy work”. It’s crucial for leadership to facilitate these processes through internal automation as much as possible. Every extra step creates a risk of someone not following the process properly, or at all.

Projects

Hands-on engineering work is the kind that requires periods of unbroken focus time. Every instance of broken focus or workflow is a danger to job satisfaction and progress. Pain points for time management not only include meetings, and queries from coworkers, but also context switching between tasks: both long and short term. Consider the kinds of tasks that one can switch between every few hours, days, weeks. The most ideal project allocations are 100%: every combination of smaller allocations will decrease productivity and toil. Two 50% project allocations don’t add up to 100%: rather, 120%.

You can identify some of your pain points in this section by asking yourself:

- How difficult is it for an engineer to create a fresh environment and deploy infrastructure? How long does it take and how many people does she have to talk to?

- Do you use engineer-friendly systems? How do you know?

- Are regular company processes automated? For those processes that remain manual: how many steps does it take to complete it from beginning to end?

- How much documentation is there around policies and onboarding? How much of it is transferred through word of mouth? How realistic is it that every engineer knows all of it and is up-to-date on every change that’s made?

- Do engineers get disrupted often? Are internal meetings flexible in timing? Is engineers’ time maximized for heads-down work?

- How often are engineers overallocated? Are the same ones consistently doing this? Is the business need clear and obvious?

- Do engineers enjoy the work they’re asked to do?

- Is there a feedback loop for engineer satisfaction? (More on this at the end)

Growth

When we talk about growth, we’re referring to personal and professional growth an engineer can take home and use in the future. All members of an organization should always be motivated to grow their skills: social, business, and technical. It’s understandable that this may not happen every single moment of a given time period, but when one looks back at a time frame of quarters and years, growth should be obvious to both the leadership and the subject.

For engineers, a big part of growth comes from direct management: through motivation, and clarity of business needs. Immediate managers have to be deeply and closely involved in people management: without this core practice, growth is entirely on the shoulders of their reporting engineers, who may or may not have insight of business needs or direction. The most basic practice of regular 1:1s is too often ignored by managers: while some engineers can find their own path, others cannot, and will be left stagnating. It’s up to the managers to ensure that their reports know exactly where and how to grow, until they develop that skill for themselves.

Growth can be both internally and externally visible: both are necessary. Internal visibility is success in the role: bringing in a difficult client, delivering a knowledge-sharing session, creating novel intellectual property. Examples of externally visible growth are regular blog posts, Github account activity, attendance of conferences and meetups, promotions. Widely shared, external visibility will reach internal circles and benefit the engineer in company growth; the inverse applies. When such bidirectional sharing isn’t possible (for example, when external growth isn’t useful internally, or when security clearances are in effect, preventing sharing of internal successes), maximizing both internal and external visibility are necessary to ensure engineer growth.

Maintaining professional visibility is often overlooked: it is, however, a crucial part of today’s market, used by both internal and external stakeholders to gauge experience and skill set. When an employee and their successes aren’t well-known internally (either because of lack of business impact or a lack of their leadership publicizing it), that marks them as unnecessary. When an engineer’s visibility isn’t obvious externally, it harms their future employment prospects.

All parts of an organization are responsible for engineer growth: Engineer Managers, Upper leadership, IT Support, and Human Resources are all accountable for availability of R&D environments, learning materials, and learning and development funds to facilitate growth.

Some questions around this section are:

- Is there a regular feedback loop on the following subjects:

- Immediate people management: effectiveness, growth enablement, regular 1:1s

- Motivation of personal growth

- Clarity of business needs and direction

- (More on this at the end)

- Are there clear metrics for measuring People Managers’ performance?

- Does upper leadership have clear buy-in for growth, learning, and development? Is it effective?

- Are engineers both internally and externally visible? Is there a discrepancy of whose reports are more or less visible? Is there a leadership problem or an individual contributor problem?

- Are engineers enabled to be externally visible: do they have Technical Writer support, do they use their personal Github accounts for work?

- How difficult is it to spend learning and development funds? Are there boundaries or difficult processes?

- How difficult is it to create and use a research-and-development environment?

Compensation

At the top of the pyramid is compensation. When we’re talking about increasing or decreasing it from a set target, that target is market value. While this is the factor simplest for leadership to provide, it’s also the least impactful attribute for an engineer’s long term commitment to the role. Consider an engineer whose other needs in the pyramids are unfulfilled: their communications are lacking or toxic, their day-to-day is full of tedious manual processes and repetitive tasks, they don’t feel like they’re growing skills. This causes stagnation, ignorance, lower quality work, which ideally causes the engineer to leave before they lose too much of themselves.

While this category is least valued, it’s still necessary. In the current state of affairs, it’s expected that engineers discuss their salaries with their peers and senior members of the company, as well as outside it. Resources like Levels.FYI, H1B Salary Database, GlassDoor are available for everyone to find their approximate value in the market. Your most valuable engineers (confident, skillful, with excellent business acumen) tend to be the best at ensuring their growth and at interviewing, putting them the best position to leave.

There must always be a clear reason for differences in compensation: market turmoil is not a good reason to pay some of your engineers more than others. If a company has the cash flow to hire new engineers to perform more work, it has the cash flow to increase existing salaries. Note that such fluctuations can be covered with bonuses or stock offerings rather than base pay, and extra technical needs can be filled with contractors rather than FTEs (Full Time Engineers). There are benefits and losses to all parts of this equation.

Some questions you should ask yourself are:

- What are engineers of comparable levels earning at different companies, including base, bonus, and stock? What could a given engineer, with their skill level and social skills, be earning elsewhere?

- Do your people managers have visibility and control of their reports’ salaries?

- Does everyone in your organization have a clear understanding of the reason for disparity in their compensation, whether low or high?

- Do engineers’ raises have clear parity with merit?

Feedback process

You’ll notice how often I’ve used the word feedback in this proposal. Three of the four most important parts of the pyramid are largely supported by a constant feedback loop:

- Solicit feedback through anonymous survey.

- Provide the findings to upper leadership, through Human Resources for any necessary filtering or rewording to ensure leaders can’t retaliate against their reports.

- Discuss the findings with direct leaders: positive feedback should be public, negative feedback should have engagement and follow-through.

- Discuss all filtered feedback with the engineers: present improvement plans, provide regular updates.

- Repeat regularly, depending on severity.

Finally, everything in this proposal depends on all levels of the company hierarchy: Engineers, People Managers, Upper Leadership. All three groups, all individuals have to be on-board.

DevEx

This isn’t DevEx (Developer Experience): a discipline of maximizing engineer performance through quality tooling, automations, and Technical Operations support. This is an expansion on the DevEx philosophy focusing on what leaders and engineers can do to have the best experience working in an engineering department.

Further reading

Here’s some further reading on adjacent ideas:

- What is Developer Experience (DevEx)?

- Developer experience: What is it and why should you care?

- Survey reveals AI’s impact on the developer experience

- The two types of quality

Conclusion

If you read this far, you probably care about your organization’s engineering culture. I’m available on a full-time and contract basis to help you: shoot me an email!

Slava I. Maslennikov

Cool Consulting, LLC

you're not your job you're not how much money you have you're not the car you drive you're not the contents of your wallet you're not the opinions of your company and neither is this site